Abstract: In this essay I plan to demonstrate that both of Euclidean Perspective (Also known as Linear Perspective) and Optical Science has placed an inspiring paradox for painters pursuing Objective Reality Depiction, for this I will review important aspects of the evolution of both tools, finding shared connections and looking at the reactions that they generated in the work of three mayor painters; Diego Velázquez, Pablo Picasso and David Hockney, at the end I will conclude that great painters seeking a realistic representation of the world have been and will keep recurring to this kind of technologies and their challenges.

Key words: Linear perspective, collage, optical projection, mirror, painting.

As a realistic painter I know that when you reflect about the challenges of reality depiction through painting, it is unavoidable thinking about linear perspective, it`s fundamental principles are taught to us in the school and it seems to be everywhere you look; you see evidence of it in photos from Street advertising, on printed magazines and papers, you see it on the digital images in the screen of your computer, when you search the internet, on your social networks and even in the image gallery of your mobile phone, this concept is so embedded inside of our brains, that most of the time we take it for granted.

History has shown us that, Since the Renaissance, had been presented with the challenge of representing a three-dimensional reality over a two-dimensional space, and it is often believed that the invention of linear perspective offered a permanent solution to this problem. In this paper, I will try to show you that this belief is far from the truth, that there is enough evidence to prove that this challenge was not solved in the renaissance nor in the present day.

In the present text, I pretend to take the reader on a trip through the most significant moments in the history of linear perspective, I will start with its origins as a system for the objective representation of reality, then I will continue a chronological analysis focusing on taking a look at the work of major figures of painting i.e. Diego Velázquez, Pablo Picasso and David Hockney.

My main goal with this essay is to demonstrate that as the use perspective systems and optical science, has challenged painting in many ways, and great artist had found very different ways to liberate from the oppressive contradictions of objective representation.

THE CONNECTION BETWEEN LINEAR PERSPECTIVE AND OPTICAL DEVICES

Depicting an objective view on the world

The Renaissance is commonly considered as an exuberant artistic period of western civilization, a period driven by the rediscovery of classical Greek philosophy, A way of thinking that influenced the whole structure of society. According to Paul M Laporte, The notions of philosophical empiricism were widespread around the Renaissance and supported the belief that painting was a reflection of the objective world, This challenged and inspired painters to produce more “realistic”, more “objective” and more “scientific” paintings than ever before in the history of art, this gave birth to the naturalistic painting, and this way of thinking remained as almost immutable until the beginning of the nineteenth century (Laporte, 1951).

One of the biggest achievements of Renaissance painting was the development of Linear Perspective, a spatial system that allowed the artist to objectively depict reality over a flat surface. Its invention has been commonly situated between 1413 and 1425 and attributed to Filippo Brunelleschi, an Italian architect and sculptor that lived around Early Renaissance. According to Malcolm Park, Brunelleschi is accountable for revealing perspective’s basic “rule” i.e. that Vanishing points for parallel horizontal lines exist at the eye level to prove this, the author recreated the same technique deployed Brunelleschi; a panel and a mirror where held inside a camera obscura that allowed him to project and correctly depict the Baptistery of San Giovanni. In 1435, a few years after Brunelleschi achievement, Leon Battista Alberty published his treatise on painting and perspective De picture, were he “demonstrated how a perspective view could be constructed by geometrical means” (Park, 2013). Although there is fairly enough evidence of Brunelleschi`s achievement, there are convincing findings that place the origins of the linear perspective way back and inside the Greek culture.

Narcissus and the origin of Objective depiction

In the introduction of his essay; “That Depictive Line: Plato, Linear Perspective, Visual Perception, And Tragedy”, Jeremy Killian refers to the findings presented by Samuel Edgerton in his book “The Renaissance Rediscovery of Linear Perspective”. According to Killian, Edgerton provides sufficient evidence to support the idea that Brunelleschi did not invent the three-dimensional style for the representation of the world on a flat surface, but in fact, re-appropriated the knowledge of many earlier cultures, he points out that there is important evidence inside the extant work of Vitruvius, a renowned Roman architect from the second century AD. According to Edgerton, in Vitruvius’s writing De Architectura, while referring to the specific details of an Ancient Greek play, it is mentioned the use of a “backdrop” that hung behind the actors and is even possible to find details about a geometric system of portrayal: “a fixed centre is taken for the outward glance of the eyes and the projection of the radii, we must follow these lines in accordance with a natural law . . . what is figured upon vertical and plane surfaces can seem to recede in one part and project in another” (Killian, 2012 – P89).

Further into the text, Killian reviews references to linear Perspective inside of two of Plato’s writings; first he refers to the Book X of The Republic, where Plato reflects on the inconvenience of the painting of a bed versus the actual bed, The Greek Philosopher complains that the painting “touches a small part of each thing”, meaning that there is a huge loss of visual information when the image is compared to the actual object. Finally, Killian also reviews Plato`s dialogue The Sophist where he reflects on the images generated from two types of sculpture; i.e eicastic images that “correspond mathematically to reality” and phantastic and inferior ones who seem to portrait three-dimensional world thanks to the manipulation of the viewer`s perception. In this case, Killiam easily connects Plato’s observations with the geometric principles used in painting (Killian, 2012 – P89).

Now let’s take a look on a complementary approach on this matter; In the book “Perspective in the Visual Culture of Classical Antiquity”, Rocco Sinisgalli also reviews different sections of these books; in the case of Book X, Sinisgalli highlights Plato`s pronouncements on images reproduced by means of mirrors; “he states that if one takes a mirror and turns it from side to side, it will quickly reproduce the sun, the stars, the earth, ourselves, other living beings, furniture, plants, and every other object”. (Sinisgalli, 2013 –P9). And When referring to The Sophist, Sinisgalli states that Plato calls “images” both what is reflected on the water and in mirrors and things which are “painted” or “modelled”. (Sinisgalli, 2013 –P10). This lack of distinction between reflections and both paintings and sculptures, other comment found on Killian`s text, allow space to conclude that Plato somehow mistrusted the illusion of the depicted image on a flat surface as it might offer little information about what was seen by the spectator from a fixed viewpoint. On this matter, Killian also includes a quote from Descartes`s The Phaedrus; “the offsprings of painting stand there as if they are alive, but if anyone asks them anything, they remain most solemnly silent.”

It is fair to argue that this shared mistrust for both reflections and both paintings and sculptures also suggest that they might have a lot in common. In a previous part of his text, Sinisgalli also refers to the need of ancient humans to fix the image on the mirror and connects this challenge with that of the linear perspective. “The Greeks and the Romans rendered objective the desire to imitate nature by operating in conformity with a theory of flat nondeformed mirrors and not in conformity with the simple observation generated by the eye” (Sinisgalli, 2013 -P8).

Up to this point, it is fair to say that although the origin of geometrical perspective might be attributed to the Greeks, it was only until the Renaissance that it was embraced as a fundamental symbolic form for the objective depiction of the world. It is also fair to say that its origin is shared with that of Optics science.

A collage of systems.

Although the Renaissance period has been abundantly studied and documented, a fair amount of misconceptions about fundamental topics still awaits to be cleared. In his research paper “Renaissance Perspectives”, James Elkins tries to clear several misleading assumptions about Linear perspective. For the purpose of this paper, I will draw the attention to a specific one; “The idea that linear perspective proper is a way of unifying pictures or pictorial space”. He suggests that this is an idea developed after the Renaissance because artists from this period actually saw perspective methods as a useful tool for the depiction of individual objects rather than a system to establish “the “infinite, isotropic, homogeneous” Euclidean space” (Elkins-1992, p209 – 210). As an example, Elkins does a closer inspection of Giorgio Vasari’s work and shows how the artists did not consider linear perspective as a unifying system for the composition and were attracted by the idea of using it to depict several objects and even conceived that a painting could be “full of perspectives” (Elkins, 1992). This revelation might suggest that at least one artist from the Renaissance was using Linear perspective in a peculiar way, not as a whole system but rather a collage of them. Before continuing, Before continuing, I would like to point out that underneath this fragmented use of Linear perspective, lies a fundamental contradiction because instead of ensuring the Objective depiction of reality, perspective is being used to conceal the lack of it.

To add another layer to this matter, let`s take a look into the Hockney-Falco thesis. When it was published in the year 2000, it generated a huge controversy inside the art world, especially among art historians because it challenged the commonly accepted ideas about how Old Masters made their masterpieces; this thesis presented convincing evidence to support the idea that in the year 1425, while Fillipo Brunelleschi was painting his first piece using linear perspective, other big artists like Jan Van Eyck and Robert Campin were using either concave mirrors or refractive lenses to project onto their canvases the images of objects illuminated by sunlight (Falco, 2009). So it is fair to assume that these artists were able to copy real-life projections without dealing with the complexities of the perspective system and obtained quite impressive naturalistic results. This thesis also presents evidence that might aloud to conclude that pieces like “The Arnolfini Portrait” by Jan Van Eyck and “The Ambassadors” by Hanks Holbein the Younger, were not painted under a unique compositional system, but in fact, are the end product of a collage of several ones i.e. some parts were painted with the aid of optical projections while other parts were painted from direct observation.

It is also important to say that on the Hockney-Falcon thesis also states that there is evidence that suggests that many big modern artists continued the tradition of using optical devices for the production of their masterpieces and that this tradition has been perpetuated by the invention of photography.

So let`s think for a moment; by the early Renaissance, some Dutch artists knew how to use optical devices while an Italian artist was using a camera obscura to correctly depict a Baptistery, there is also evidence of the use of several perspectives inside a painting and also paintings built as collages of different techniques. Taking all of this into account, it is possible to conclude that since the Greeks, both Linear perspective and Optical devices have been used as tools for the objective depiction of reality.

Painting like a Cyclops.

One of the fundamental assumptions of Linear perspective is that the viewer is located at a fixed point outside an in front of the flat surface, the whole system is based also on one simple yet problematic assumption; the viewer has only one eye. A similar inspection on the optical devices used to project images onto canvas, like the camera obscura and the camera lucida, reveals that they also share this monocular view and needed a still motive in order to facilitate an accurate translation of the projected image. Both static position and monocular vision are opposite to the way most humans experience reality, therefore this challenges the very notion of objective depiction. One look at history will also explain why this question still relevant today.

Around the middle of the 18th century, a mayor discovery changed both the scientific and artistic scene, in the year 1839, Louis Daguerre was able to chemically fix a projected image of a street scene. This event marked a turning point for western image production and especially for the objective depiction of reality. Contrary to the common belief that photography was possible thanks to the invention of the camera, it has been acknowledged as a chemical invention. On a recent interview, David Hockney made this clear while talking about the relation between painting and photography, he expressed that he had never accepted the idea that painting will be challenged by photography, he also added that photography was born from painting as painters had known about projections since the Renaissance and the use of the camera obscura, by the end of his statement he said “some photographs might have been made before 1839, but they wouldn’t have lasted, they would have faded… Fox Talbot asked Sir John Herschel and Herschel gave him the formula for the fixative…That was the invention” (Hockney, 2016 – 69).

It is fair to say, that modern painters who embraced photography also had to deal with the same contradictory principle, it is also important to acknowledge that since the Renaissance these tools have been intensely used and both their advantages and challenges had been embraced by great artists in many ways. To expand this idea, I will dedicate the next lines, to review one specific painting from three major figures in the recent history of painting.

Challenging the viewer, Diego Velasquez

In 1656, Diego Velázquez finished the painting what is considered his masterpiece; “Las Meninas”. Although there has been a lot of discussions about its technical qualities, the main attention has revolved around it’s meaning thanks to the complexities of the composition. In her book, “Picturing Space, Displacing Bodies”, Lyle Massey goes through Michael’s Foucault reflections on this painting; he refers to it as a true testimony of the inherent paradox inside the classical episteme; the philosophical empiricism and it`s the quest for objective reality. Massey points out that this painting confuses the presumed connection between the view from the painter and that from the viewer. She states that thanks to several misplacements, the painter destroys the classical conception of the point of sight; first, he keeps the spectator from filling the position of the artist as the painter is both pictured inside the painting and outside watching the painting, and then he misplaces the spectator because now he is occupying the place that rightfully belongs to the King and The Queen. Whit out a doubt, whit this painting Velázquez challenges the Linear perspective system with a unique collage of intersected perspectives.

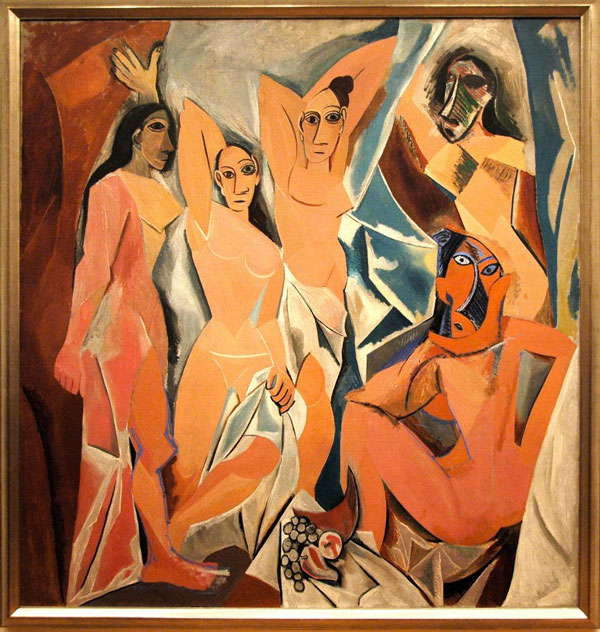

Scaping the Euclidean space. Picasso

In 1907 Pablo Picasso finished the painting Les Demoiselles D’avignon, a work of art that is “probably considered the first truly twentieth-century painting” (Fry, 1966 – p12) as it challenged two of the most valuable characteristics that European painting had guarded since the Renaissance: the classical cannon on the human figure and the spatial construction through the linear perspective (Fry, 1966 – p13). It is important to notice that in that same year, the Cubist movement flourished in Paris and when even farther as it developed its own spatial approach.

As a very interesting fact, while Picasso, was in Paris finishing his iconic painting, the German art historian Oskar Wulff coined the term “umgekehrte Perspektive” or “reverse perspective” on an essay where he was reviewing the construction of space in Byzantine Icon art. Since then, four different and conflicting thesis about this matter have circulated but for practical reasons I am only going to refer to “the Optical View Thesis” on the Reverse Perspective system, this thesis holds the same affirmation of that from David Hockney when he refers to Cyclops: “Optical view thesis is proposed by a number of studies that have attempted to prove that reverse perspective is somehow true to the way human vision actually functions”. (Hockney, 2016 – 69). Although it is not possible to draw a direct connection between the theory behind reverse perspective and cubism, it is possible to state that the beginning of the 19th century was marked by a strong challenge to monocular representation systems and cubism was an artistic movement that pursued the representation of reality as a different collage of multiple points of view.

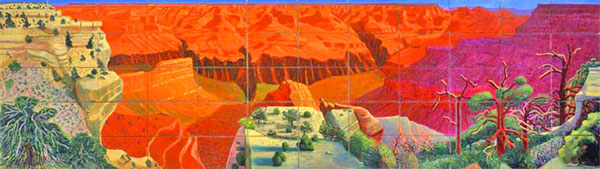

Seeing with multiple eyes, David Hockney.

It is important to say that David Hockney makes extensive use of photographs in his work and has even created marvellous pieces of work while exploring the use of photography, like his series of “photographic drawings” and “photographic collages”, it is important to keep this in mind to understand the context of the next quote, and to make a connection with the next concept I would like to approach in this paper, reverse perspective: “ photography is all right if you don’t mind looking at the world from the point of view of a paralyzed Cyclops” (Hockney, 2016 – 69). Here Hockney is referring to the monocular system explained. To connect with the concept of reverse perspective and explore his own approach to a binocular representational system, Hockney has done many “photographic drawings”, in this pieces he mixes and overlaps many close-up images from different parts of the subjects, so at the end, the whole scene is built by combining sometimes hundreds of individual images each one with its own vanishing point. He also has used this same technique to build his large scale painting of the Grand Canyon “A Closer Grand Canyon” a piece he made around 1988. It is fair to say that this practical approach represents another version of the collage approach discussed in the work of Velázquez and Picasso.

Conclusion

Painting is the result of the human need to represent and even copy nature, therefore, objective representation has been an antique desire that has challenged human minds and motivated many inventions, it fair to say that the origin of the perspective system and optical science is related to this quest. Science keeps making great contributions not only to the way we understand the world but most importantly, the way we depict it. The history of realistic painting shows that great minds had challenged the monocular representation system in many ways.

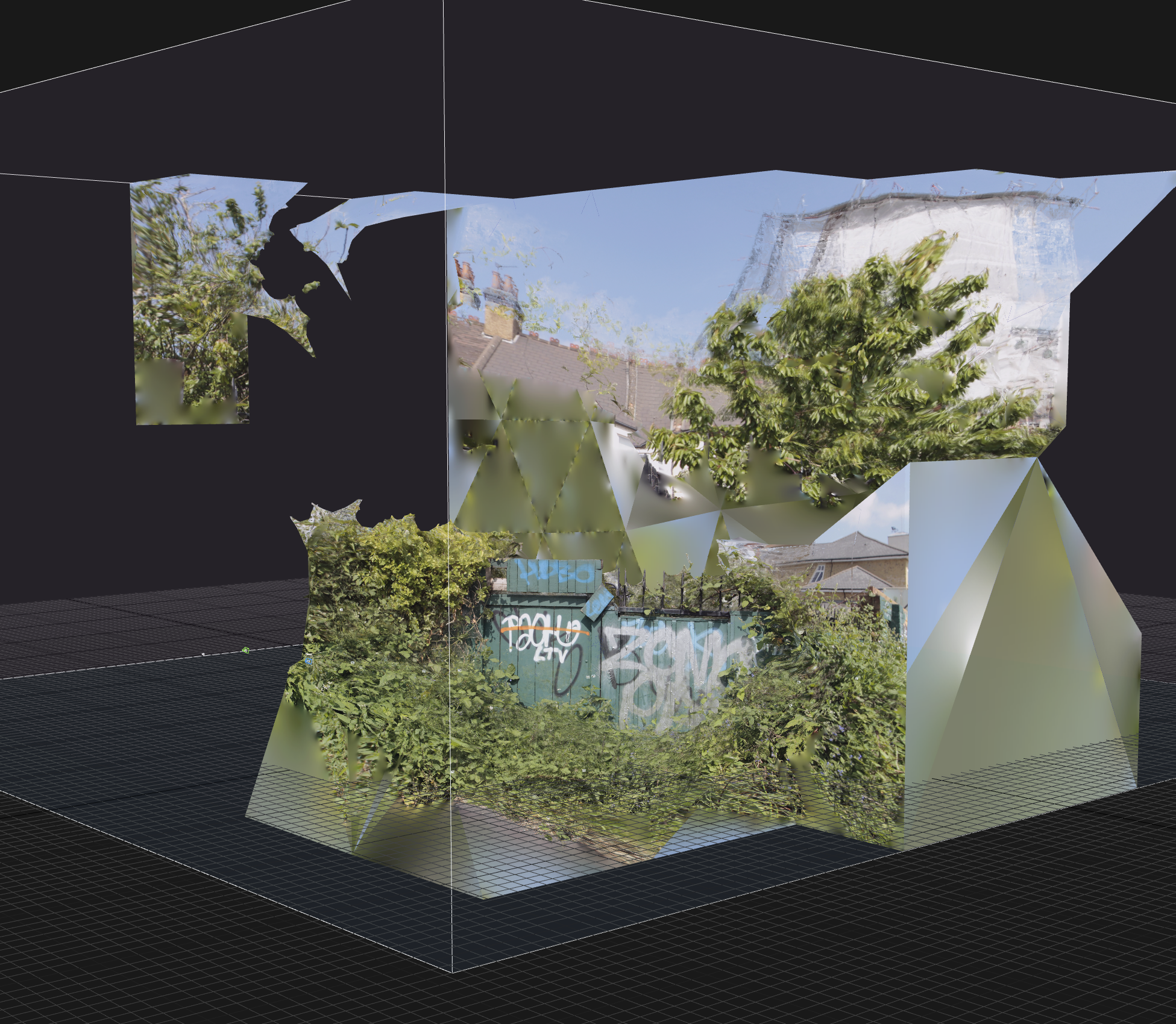

Nowadays, digital photography, 360 cameras, photogrammetry, projection mapping, holographic technologies, VR and AR are challenging the monocular structure of the image, it might be that this changes will allow the expansion of painting even outside of the collage approach. It is to soon to tell, but the long history of painting might certainly indicate that if reality depiction technologies evolve, painting will follow and challenge them.

Bibliography:

Melchior-Bonnet, S. (2002) The mirror. New York: Routledge

Sinisgalli, R. (2013) Perspective in the visual culture of classical antiquity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Killian, J. (2012). ‘That Deceptive Line: Plato, Linear Perspective, Visual Perception, and Tragedy’. Journal of Aesthetic Education. 46(2), pp. 89-99.

Park, M. (2013). ‘Brunelleschi’s Discovery of Perspective’s “Rule”’. Leonardo. 46 (3), pp. p529-265

Minneapolis Institute of Art (2009) Charles Falco: The Tyranny of the Lens. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Kuk3wDMl_0Y (Accessed: 1 August 2016).

Hockney, D. and Falco, C. (year publication) ‘Optics and the old masters’ Annual Meeting of the Optical Society of America: subtitle, Organisation or company, Location, October 11-14. Year event

Hockney, D. and Falco, C. (2003) ‘The Art of the Science of Renaissance Painting’ Proceedings of the Symposium on Effective Presentation & Interpretation in Museums: The National Gallery of Ireland, Dublin, date of Conference.

Hockney, D. and Barringer, T. (2016). David Hockney – 82 portraits and 1 still-life. London: Royal Academy Publications.

Elkins, J. (1992). ‘Renaissance perspectives’. Journal of the History of Ideas. 53(2), pp. 209-230.

Gray, C. (1953) Cubist Aesthetic theories. London: Oxford University Press.

Fry, E. (1966) Cubism. London: Thames and Hudson.

Antonova, C. (2010). ‘On the Problem of “Reverse Perspective”: Definitions East and West’. Leonardo. 43(5), pp. 464-469.

Laporte, P. (1951). ‘A Cultural Evaluation of Subjectivism in Contemporary Painting’. College Art Journal. 10(2), pp. 95-109.

Massey, L. (2007). Picturing space, displacing bodies. Pennsylvania: The Pennsylvania University Press.